In the UK we have a criminal legal system which requires the burden of proof to be “beyond reasonable doubt” – should any doubt be present then the defendant should be acquitted of any charges. You already knew that.

The way the system works is a witness will be questioned by their own counsel and then cross examined by the other side. The idea here of course is to determine the facts of the case and convince the jury (if present) that something did or didn’t happen, how it did or didn’t happen and to prove or disprove the charge. The questions can often be difficult and since most barristers are cunning, the questions will also be worded and crafted in such a way as to get the answer the particular barrister wants. But you already knew that too.

It is quite fun to watch when this kind of thing happens. You can see how answers are manipulated and in many cases the witness will become frustrated, making them even easier to question. This is fine if the witness is a horrible criminal – you want to see them have a hard time – but what if the witness is the victim or someone who is vulnerable? Fine if they’re a hardcore robber but what if they are a young rape victim?

I have just finished watching a Panorama documentary on how rape is dealt with by the legal system (good old BBC making it available for free online). I didn’t watch this because I was told to, although the consideration of consent turned out to be completely relevant to what we are currently looking at in our Criminal Law seminars at the moment). The points raised were quite interesting in that whilst our legal system does indeed ensure (for the most part) that if someone is convicted then they are actually guilty, but the way it works in sensitive cases such as rape raises some important questions.

The documentary mentions that in many rape cases it is just a question of the word of one person against another, and usually the victim is highly traumatised by the incident and may have even been drugged or intoxicated and thus unable to remember anything. In these situations the only evidence is that provided by the defendant who is not going to admit to what actually happened. If there is no evidence to suggest otherwise – no video cameras, no witness and no credible testimony from the victim because s/he was drunk – whilst it might not be what you want, the only legal response is to aquit. There is doubt as to what happened and the burden of proof is clear.

Based on these factors, the first point that must therefore be considered is how counsel questions victims in such cases. Their job is to win for their client and you often read how lawyers are heartless monsters who will do anything to win In reality, they are actually real people and I would even suggest most lawyers have their own moral code! How do you deal with such a sensitive issue when the only real defence is to bring into question the credibility of the victim?

From Panorama:

The defence counsel’s strategy in these cases is to undermine the credibility of the complainant. Sometimes this is done in a very heavy-handed way, you know, by dragging in her sexual past. Sometimes it’s done rather more subtly. But it doesn’t matter which way it’s done, that is the strategy. To suggest to the jury that this woman, who is telling you this story, well perhaps she’s not entirely credible. – Jennifer Temkin, Professor of Law – University of Sussex

But wait, is “victim” the correct term here? Is our legal system not based around the principal that the accused is innocent until proven guilty?

Yes, true, but I think that’s a technical legal point that isn’t really relevant in the actual treatment of the victim…or alleged victim.

So what do we do?

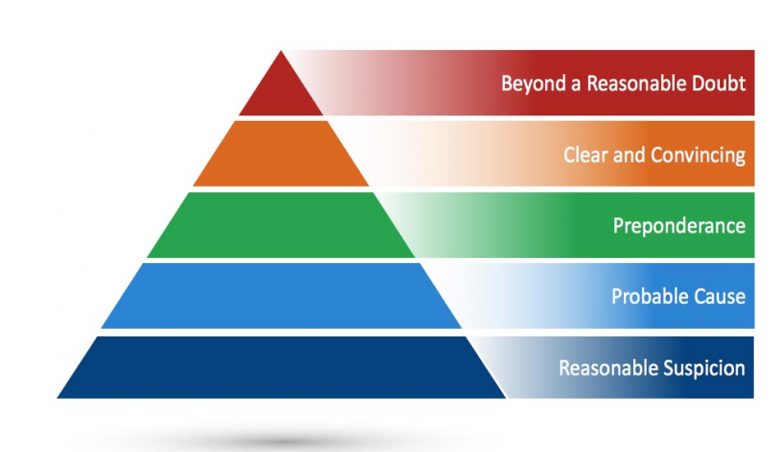

Perhaps looking at the second point will help with the dilemma of the first? The burden of proof. If it is really just down to the word of one against another does that not mean that the jury has to weigh up the probability of whether the testimony of the one is more likely to be true than the other? How likely does it have to be for the jury to consider it to be true beyond all reasonable doubt?

The question is therefore should we make an exception in the case of rape to the burden of proof and change it so that the burden of proof is like civil cases – the balance of probability?

If you change the standard of proof just to get a conviction, what will happen is you will have innocent people going to prison, and probably sitting in prison for years, for something that obviously they haven’t done. I think the balance always has to be to ensure that innocent people don’t go to prison. Our system is revered around the world as being a fair system, and unfortunately if that means that guilty people walk free, then that is the price you pay for ensuring that an innocent citizen isn’t locked up for many many years. – Kirsty Brimelow, Criminal Barrister

As a law student learning in detail how the system works, I think these are good questions that students should be considering – how the legal system has been built up to handle these cases and how well it does it, especially if many students are going to go on and be involved in these kind of issues.

So what should be done?